A more nuanced understanding of the relationship between corruption and development is needed to assess the impact that philanthropy has, and could have, on the governance environment in developing countries.

When we think about the barriers to economic growth in developing countries, one of the first that most people will think of is corruption. The notion that tackling corruption, or rather promoting the rule of law, is key to facilitating development has been at the heart of the international development orthodoxy ever since the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 demonstrated that fiscal policy and market liberalisation alone, could not guarantee stable growth.

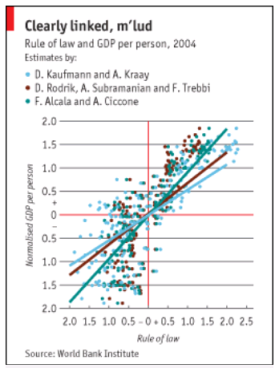

Though belief in the rule of law as a panacea for development has waxed and waned for a generation, the evidence for a relationship between economic growth and good governance is incontrovertible. The eminent economist and former Director of the World Bank Institute, Daniel Kaufmann has, with Aart Kraay produced a wealth of research that links economic progress to improvements in controlling corruption. Using data from the Worldwide Governance indicator set Mr Kaufmann claims to be able to demonstrate that per capita income rises by 300% when a nation achieves an improvement of one standard variation in the Worldwide Governance Indicator scoring system. Chile for example, is 300% richer (per capita) than India and scores one standard variation higher.

Chart taken from an article in the Economist (Order in the Jungle, March 13th, 2008) comparing the relationship between rule of law indicators and development in 3 different studfies

Working in international policy for Charities Aid Foundation and thinking about the role of philanthropy in development and the barriers to its growth, I can testify that this understanding of corruption influences a lot of the debate. Development experts are split between a majority who see philanthropy as crucial in eradicating corruption and a minority of sceptics who see charitable funds as being at particularly high risk of money laundering and graft.

By and large the first group identified above see civil society as having the capacity to improve the governance situation within developing countries by holding those in positions of power to account and exposing corruption. Indeed, the United Nations, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank have all focussed on the potential for civil society to play a role in combating corruption. In this view, as the organisational embodiment of civil society, not-for-profit organisations are uniquely placed to play the role of critical friend to the powerful. However, there is also a perception in some quarters that not-for-profit organisations are part of the problem rather than the solution.

In nations where most not-for-profit organisations remain under the radar of regulators or where regulators are either under resourced or lack the authority to validate governance – fear of corruption is a serious turn-off for donors. In reality, there is no evidence to suggest that not-for-profit organisations are a greater risk for corrupt behaviour than any other sector – indeed, there are good reasons to suspect that the reverse may be true – but in the absence of scrutiny some people will seek to abuse the system. It is for this reason that CAF undertakes extensive checks of donors and charities and offers validation services for cross border donors.

The debate turned on its head

Personally, whilst siding very definitely with the first group, I do also accept that not-for-profit organisations are not immune to abuse. Indeed, having spent a great deal of time researching regulatory policy for the Future World Giving report, Building Trust in Charitable Giving, I am a strong advocate of more effective regulation. But I, like many others, have been wrestling with how to convince donors (and politicians for that matter) that the net effect of philanthropy is positive in the fight against corruption? However, I am starting to wonder whether I have been looking at this from the wrong angle.

Last week I listened to a download of the excellent Development Drums podcast featuring a debate between the aforementioned Daniel Kaufmann and the heterodox economist Professor Mushtaq Khan. In the podcast, which was recorded back in 2009, Khan turns the assertion of Kaufmann and mainstream thinkers – that corruption is a drag on economic growth – on its head by suggesting that good governance is the product of economic development rather than a causal factor. He cites his research into the development of Asian countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, South Korea, Japan and China in which the development story does not suggest that reducing corruption was the trigger for economic growth.

Indeed, Khan contends that; “There’s no historical evidence of a country which first reduced corruption and then developed” and claims that our understanding of the relationship between corruption and development is overly simplistic. In Khan’s view, the idea that poor countries have higher levels of corruption because poverty is a greater incentive for rule breaking does not stand up to scrutiny. Khan says that “actually if you look at poor countries, the poorest people are not corrupt at all. It’s not the poor who are corrupt […] the question really is why are emerging ruling classes in poor countries so corrupt compared to ruling classes in rich countries?”

The answer to this compelling question, according to Khan, is that high levels of corruption are an inevitable consequence of the social transformation that takes place as an economy grows. He argues that at a certain stage of development, those newly enfranchised by wealth and power will seek to solidify their positions in society through what economists call “rent-seeking behaviours”. Rent-seeking is essentially any method of acquiring existing wealth, as apposed to creating new wealth through economically productive activities. In wealthy countries, the richest are able to benefit from legal forms of rent-seeking through wealth management activities and particularly effective tax management – both of which are profitable for the individual, but not productive for the wider economy. Crucially, as countries reach a certain level of wealth they are able to appease greater and greater shares of the population through the most sophisticated rent-seeking mechanism of all – redistributive taxation. According to Khan, it is only at this point that corruption can be reduced.

Redefining the relationship between philanthropy and corruption

So what does Professor Khan’s understanding of the relationship between corruption and economic development mean for philanthropy? Well, firstly, by essentially suggesting that corruption becomes systematic at a certain stage of development, it means that we can’t be complacent about whether not-for-profits are at risk of financial abuse. They will be subject to the same attempts to appropriate wealth as any other sector in the economy – not more so, but probably not less so either. As such, donors should reward organisations that have good governance arrangements and provide clear and transparent financial reports as well as advocate for better regulation.

For me, the most important message in Khan’s argument for philanthropists is that they can provide a legal and legitimate form of rent-seeking in advance of the government being capable of doing so through the tax system. Perhaps philanthropists should aim to promote healthier rent-seeking by advocating for or providing social protection programmes, care for the elderly and education and healthcare services. It might be that as people begin to enjoy a share of existing wealth through these mechanisms, their motivation for engaging in illegitimate means of rent-seeking will diminish. Seen in this way, the capacity of philanthropy to tackle corruption is far greater than funding governance training projects and scrutinising public data – as important as those activities surely are. Philanthropy can tackle the underlying cause of corruption by giving the aspirant, but as yet disenfranchised skin in the game.

But – and this is not a thought that I feel comfortable with – perhaps we have to settle for philanthropy being the least imperfect tool for minimising corruption in a context where corruption seems to be a necessary phase in development. When we give, or our government gives on our behalf through foreign aid or through tax incentives, we tend to hold recipients to the very highest of standards. That is understandable, because giving is an emotional as well as a financial transaction. However, given the apparent inevitability of corruption we need to get things into perspective because an extreme aversion to corruption could see us punish a great number beneficiaries severely for the transgressions of a minority. Bill Gates makes the point rather more eloquently than I can in his 2014 Annual Letter when he says;

“I’ve heard people calling on the government to shut down some aid program if one dollar of corruption is found. On the other hand, four of the past seven governors of Illinois have gone to prison for corruption, and to my knowledge no one has demanded that Illinois schools be shut down or its highways closed.”

But while we should make sure that when we hear about cases of corruption in not-for-profit organisations we shouldn’t tar the whole sector with the same brush, we should strive for improving standards of governance and do our best to make them a reality by ensuring that our donations are not misappropriated.

Adam Pickering

well, one great start would be if global philanthropy instituted standards that made transparency the default. That way, it would at least be harder for civil society organizations to become an instrument for corruption.

Right now, this transparency is lacking. Out of 169 think tanks we looked at, across the world, less than a quarter were highly transparent (www.transparify.org). Yet many of their donors are themselves committed to transparency.

Transparency still needs to be pushed all the way down. Once that happens, think tanks and other watchdogs will become much more credible and effective advocates for governments to be transparent and accountable, too. It’s not a silver bullet, but it’s a step that is important, and that is doable, and it could help the move towards better governance.

LikeLike

Thank you for your considered comment Hans. I think that if the goal is to root out all corruption in not-for-profits the answer would be to mainstream high standards of transparency and governance as a pre-condition for funding. However, before we even get to grips with how we would bring about such a universal compact between funders, we would have to understand, and accept some pretty unpalatable unintended consequences.

Some of the most effective not-for-profit organisations in the developing world develop out of social movements, community organisations and cooperatives . Part of what makes these organisations so important is that they enjoy high levels of trust and legitimacy within their communities. Foreign donations and grants can help to bring them to scale resulting in domestically credible and well resourced actors in civil society. However, the high levels of transparency and governance that we are suggesting should be a pre-requisite for receiving funds cannot be achieved by informal and underfunded networks. It is a chicken and egg scenario with no obvious solution. Sadly, funding outcomes necessarily involves risk.

Adam

LikeLike

Hi Adam,

thanks for your answer. Having run an organization in the Caucasus, a fairly tough context, for six years, I only half-agree. There may be imperfect institutions, and they may struggle with an audit by the likes of EY. These can be worth supporting through some mechanism. That said, there are many fairly formal institutions, with charters, accounts, contracts, and so forth, who fall short, and this ultimately damages the institutions, since running an organization well always includes sensible financial management.

Reviewing the grantees of a major Western donor, we found that 16 out of 17 organizations, including watchdog organizations, were intransparent themselves – although these watchdog organizations typically wanted government to become more transparent.

Again, having worked in these contexts, I know that there are many things that are tough to fix. This problem is *not* tough to fix, if there is a clear recognition that there is a problem (hard to deny in my view), and the willingness to actually address it.

The latter, in my view, unfortunately is sometimes in short supply. Many donors go “ooh” and “aah” when you talk about transparency, but when it comes down to them actually nudging their own grantees to shape up, we have seen the donors get evasive.

Fair enough, some of that is understandable if you have not been on the other side actually running an organization in these contexts, and you are worried about being intrusive. Yet conversely, the same circus has been going on and on and on now for many years, and it’s time to engage the donors, so that they push transparency all the way down.

Everyone (at least everyone with good intentions) will be better off as a result.

I would happily supply a guest-blog on this, in case you are interested.

Best,

Hans

——————

http://www.transparify.org

LikeLike

Reading your response I actually think there is an answer that unifies our positions. A global campaign for all funders to dedicate a minimum of, say, 5% of their grant to reporting on grants bellow say $5,000 and tapering down to 1% on large grants. This way, if donors have to fund such activities, they will start to inevitably demand high levels of reporting and will be more likely to scrutinise what they receive. The catch however, is obvious. Donors would have to increase their net donations by the same amount or funding for charitable activities would necessarily decrease.

LikeLike